Developing Emotional Intelligence

Intelligence plus character – that is the goal of true education.

- Martin Luther King, Jr.

It is one of the primary responsibilities of the school counselor to provide their students the necessary tools to be able to control their own behavior in a positive and appropriate fashion. This is what is known as EQ or Emotional Quotient. Counselors teach their students how to understand and manage human emotions, encouraging the development of “internal assets” such as integrity, honesty, restraint, empathy, decisiveness, and friendship-making skills.

John D. Mayer, a researcher and associate professor of psychology at the University of New Hampshire, and Peter Salovey, a Yale University psychology professor, coined the term emotional intelligence in 1990 after exploring the relationships between cognitive brain functions (such as memory, reasoning, judgment, and abstract thought) and affect (including emotions, moods, and feelings of fatigue or energy). They describe emotional intelligence as the ability to recognize how you and those around you are feeling, as well as the ability to generate, understand, and regulate emotions. Once labeled, the concept of emotional intelligence spread rapidly.

In 1995, Daniel Goleman, a psychologist and writer for The New York Times , expanded on the Mayer-Salovey theory claiming that the art of understanding and managing human emotions “can matter more than IQ” in determining whether a person leads a successful life (Goleman, 1995).

Focusing on emotional intelligence or the emotional quotient concentrates our efforts on encouraging “internal assets”. These assets including caring, motivation to achieve, commitment, to equality and social justice, integrity, honesty, responsibility, self-control, planning and decision-making abilities, self-esteem, a sense of purpose, and a positive view of personal future.

But the time a person reaches adulthood, emotional habits are fairly well set. To change, an adult must unlearn, then relearn behavior. So, it’s up to us as the School Counselor to ensure that we are building the child’s emotional intelligence correctly from the beginning.

Emotional intelligence works along with personally styles or traits. People can be emotional intelligent whether they are extroverts or introverts, warm or aloof, emotional or calm. It’s the development of such attributes as conflict-solving skills, self-motivation, or impulse control that proponents agree can contribute much to a child’s ultimate success. Success also involves staying centered on a positive path to avoid risk behavior such as violence, drug and alcohol abuse, tobacco use, sexual activity and others.

Hundreds of studies show that how caregivers such as parents, teachers, counselors, etc. treat children in general – whether with warmth and nurturing or with harsh discipline – deeply affects a child’ emotional life. But these caregivers can also intentionally guide children to develop emotional skills. Adults can teach empathy by simply expressing their own feelings frequently, pointing out another person’s feelings, and encouraging the child to share his or her feelings.

Children develop optimistic outlooks when they observe their parents’ optimism, says Lawrence E. Shapiro (1997). Shapiro, who frequently uses creative games to teach, suggests the “Stay Calm” game to develop anger control. While one child concentrates on playing pick-up sticks, another child is allowed to tease him in any way he likes as long as he doesn’t actually touch him. Each player gets one point for picking up each stick, and two points for showing no reaction to the teasing.

We can also use the following suggestions to encourage the development of the internal assets that build up emotional intelligence in their children.

- Helping people. Regularly spend time, whether as a family or as a school community, helping others. Volunteer at local shelters or nursing homes. Show care for your neighbors.

- Empathy. Model mutual respect in the school community. Do not tolerate insults, put-downs, name-calling, or bullying. Talk about how selfish or hurtful choices and behaviors affect other people.

- Decision-making skills. Include your students in decisions that affect them. Give them a chance to talk, listen to them respectfully, and consider their feelings and opinions. Allow for mistakes; don’t blow up at a poor decision. Instead, help them learn from their errors.

- Planning skills. Give your teenagers daily planners or date books and demonstrate how to use them. Show them how to plan ahead for long-term assignments so they’re not overwhelmed at the last minutes.

- Self-esteem. Celebrate each child’s uniqueness. Find something special to value and affirm. Express your love (unconditional positive regard) regularly and often. Treat your students with respect. Listen without interrupting; talk without yelling even if they are interrupting and yelling.

- Hope. Inspire hope by being hopeful. Don’t dismiss your student’s dreams as naïve or unrealistic. Instead, share their enthusiasm. Eliminate pessimistic phrases from your professional learning community’s vocabulary. Replace, “It won’t work” with “Why not try”. My father always told me, “It never hurts to ask” and “The worst they can do is say no”. Just this thinking provides hope.

- Assertiveness. Teach your students the difference between assertiveness (positive and affirming), aggression (negative and demanding) and passivity (vulnerable and effortless). Point out examples of these behaviors in movies, television programs, media, and the community. Teach your students to stick up for themselves instead of going along with the crowd because it’s easier.

References

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional Intelligence. City, State: Bantam Books. Shapiro, L. E. (1997). How to raise a child with high EQ – A parents guide to emotional intelligence. City, State: Harper Collins.

I am a school counselor turned counselor educator, professor, and author helping educators and parents to build social, emotional, and academic growth in ALL kids! The school counseling blog delivers both advocacy as well as strategies to help you deliver your best school counseling program.

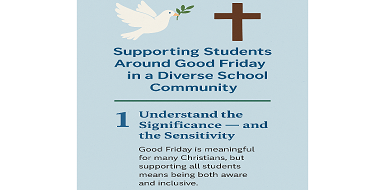

I'm a mother, grandmother, professor, author, and wife (I'll always be his). Until October 20, 2020, I lived with my husband, Robert (Bob) Rose, in Louisville, Ky. On that awful day of October 20,2020, my life profoundly changed, when this amazing man went on to Heaven. After Bob moved to Heaven, I embraced my love of writing as an outlet for grief. Hence, the Grief Blog is my attempt to share what I learned as a Counselor in education with what I am learning through this experience of walking this earth without him. My mission is to help those in grief move forward to see joy beyond this most painful time.